On a random weekend where we had some more free time, we decided to check out Eigen Network’s zkVM Github. We discovered a critical vuln in the proving algorithm that allows any user to generate an arbitrary proof for a given program. This allows for complete proof forgery and destroys the zkVM.

TL;DR

- Eigen Network has a zkVM that can be used to compile and prove Rust/Circom programs

- Missing index selection checks in fiat-shamir in FRI allow for proof forgery

- Allows an attacker to forge proofs that show arbitrary outputs for inputs

About Us

At Veria Labs, we build AI agents that secure high-stakes industries so you can ship quickly and confidently. Founded by members of the #1 competitive hacking team in the U.S., we’ve already found critical bugs in AI tools, operating systems, and billion-dollar crypto exchanges.

Think we can help secure your systems? We’d love to chat! Book a call here.

Introduction to ZK/ZK-STARK/zkVM

For this section, we can’t possibly cover everything you need to know about ZK so this will be more of a general overview with links to great resources to learn more.

A Zero-Knowledge (ZK) proof is a cryptographic protocol that allows one party (the prover) to convince another party (the verifier) that a statement is true without revealing why it’s true or sharing any additional information. The “Zero-Knowledge” aspect means that beyond confirming the validity of the proof, the verifier learns nothing else. A simple example is if you could prove to someone else you know the password to a system without revealing the password itself.

A ZK-proof has 3 main properties:

- Completeness: If the statement is true, an honest verifier is convinced by an honest prover

- Soundness: If the statement is false, no dishonest prover can convince the verifier (with negligible probability)

- Zero-Knowledge: The verifier learns nothing beyond the truth of the statement.

A ZK-STARK (Zero-Knowledge Scalable Transparent Arguments of Knowledge) is a special kind of ZK proof that takes less complexity to generate. As a result, these proofs are faster to generate a proof but take longer to verify. STARKs have larger proof sizes but do not require for both parties (the prover and verifier) to be trustworthy. Additionally, the proof can be verified without relying on any external parameters since the random values used during proof generation are effectively “public.” For a much deeper read, we suggest reading up this article: https://aszepieniec.github.io/stark-anatomy/fri.html. We will be referencing this article later on as well.

A Zero Knowledge Virtual Machine is a virtual machine whose execution can be proven and verified using a ZK proof. It acts like a normal VM but with the added property that every instruction executed can be turned into a succinct cryptographic proof.

This allows you to prove arbitrary computation “I ran this program with these inputs and got these outputs” without revealing the inputs or requiring the verifier to re-run the computation. So, instead of designing a custom circuit for every computation, a zkVM is general purpose and allows developers to write normal code which can later be proven. As we will see, ZK-STARKs are used heavily in the proving and verifying process of zkVMs.

A Brief Intro to FRI

This will start getting pretty technical so bear with us.

FRI stands for (Fast Reed-Solomon IOP of Proximity). In short, it proves the following statement

Given a large table of values over some domain, those values are consistent with evaluations of a polynomial whose degree is at most

FRI does not reconstruct or reveal the polynomial . Instead, it probabilistically ensures that such a polynomial must exist, up to a small error fraction.

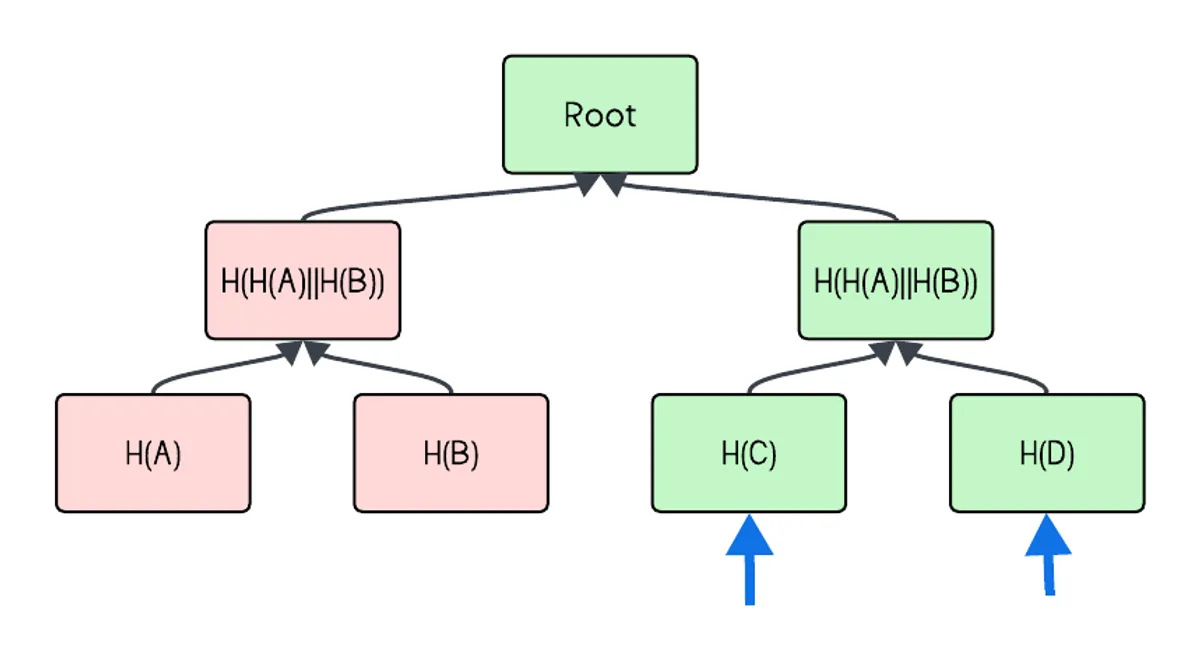

In a STARK, the prover uses a commitment (typically a merkle root) to a Reed-Solomon codeword (a set of polynomial evaluations on a given domain) and uses FRI to convince a verifier that the interpolated polynomial on the set of evaluations has a degree below a bound.

The split and fold technique

FRI works by repeatedly folding a polynomial onto itself using its evaluation table (codeword). This technique allows even a very large polynomial to be folded into a much smaller and more manageable polynomial after a couple rounds. At a high level, every round cuts the maximum degree by a factor of than the previous round. For a much deeper (and frankly, way better) explanation, please read FRI. That being said, we will run through a simple example below (summarized from the article):

We are going to introduce some important mathematical symbols now. Let be a polynomial of degree for some over some field . Assume we are given a codeword of length (also a power of 2) such that generated by . represent the multiplicative subgroup generated by a th root of unity . For this example, we will fold by a factor of 2 in the first round.

In round one, we can represent where are the even and odd indexed coefficients of . Then, we can reduce the degree of to another similar polynomial where is a random challenge. In an interactive protocol of FRI, is a random challenge value selected by the verifier. If the original evaluations came from a low-degree polynomial, then the folded evaluations should also behave like a polynomial with half the degree. This is the core idea of FRI.

This completes one round of folding as the degree from . Since the degree of has been effectively cut in half, we can also half the domain of from a length to . The domain would also change from to . Of course, all this is highly glossed over and the article linked above does a much better job of this.

Indexing

After the first round, both the prover and verifier need to perform collinearity checks on the new domain to ensure the folding from to was done correctly. The verifier samples random indices in the folded domain. For each sampled index, the prover returns the corresponding three evaluation values needed to verify the folding relation: two values from the previous round (paired points from the larger domain) and one value from the current folded polynomial.

The verifier checks that these 3 points satisfy a linear relation from the folding. If the relation holds, the fold is considered consistent at that index. Indices are sampled as many times as the fold factor requires.

Importantly, the verifier samples indices once at the beginning of the protocol. These indices are then reduced forward through each folding round. As the domain shrinks in later rounds, multiple sampled indices may map to the same point in the smaller domain. To make sure this doesn’t happen, duplicate indices are filtered out to avoid redundant checks. The remaining indices are used consistently throughout all subsequent rounds.

The Non-Interactive Version

In the non-interactive form, the index/indices for selecting which parts of the polynomial are folded is decided by a Fiat-Shamir.

The prover and verifier will use a Fiat-Shamir on the polynomial codewords to compute instead of relying on a challenge value supplied by the verifier.

At each round, the same process is repeated:

- The prover commits to a Merkle root of the folded codeword.

- Both prover and verifier compute a new challenge

- The prover folds the polynomial using and the process continues until the polynomial is reduced to a small enough degree to verify directly.

This keeps the consistency where both parties are generating the same challenge values.

Eigen zkVM

The Eigen zkVM is a ZK virtual machine created by Eigen Network (0xEigenLabs) to compile and prove arbitrary Rust/Circom programs. The zkVM provides two main approaches. Direct Groth16 proving and STARK-based recursive proving. For this bug, it only occurs in the STARK-based recursive part.

A very high level overview of the proof flow follows below:

- Rust programs are compiled into the RISC-V format and returns assembly content

- Circom circuits are compiled into the R1CS constraint system format and WASM witness calculators

- The compressor12 setup converts R1CS constraints into PIL (Polynomial Identity Language) format

- The STARK prover generates a proof and outputs both a verification circuit and proof data

- The STARK proof is converted into a Circom verification circuit, enabling recursive composition

If we look closer at steps 2 and 3, this is where the main proving logic happens. Step 2 uses something called PIL, which basically turns the circuit’s R1CS constraints into a form that can be checked using polynomials. These constraints get written into a .pil file, which tells the prover what relationships must hold between all the variables during execution.

let mut file = File::create(pil_file).map_err(|_| anyhow!("Create file error, {}", pil_file))?;write!(file, "{}", res.pil_str)?;Step 3 is where the actual STARK proof is generated. This happens in the massive stark_gen function from Eigen’s code.

- First, it sets up all the math fields and evaluation domains.

- It computes the circuit’s polynomials and extends them into a larger domain using FFTs.

- After that, it creates Merkle trees to commit to each set of polynomial evaluations, and uses the Fiat–Shamir transform to generate random challenge values from those Merkle roots.

These challenges are what make the proof non-interactive for both the prover and verifier.

Once all polynomial commitments and Fiat–Shamir challenges are fixed, the prover constructs a set of helper polynomials that enforce higher-level constraints such as lookup consistency and permutation correctness. These helper polynomials are then combined into a single large constraint polynomial, usually referred to as the polynomial. The evaluates to 0 everywhere on the execution domain iff all circuit constraints are satisfied, encoding the full correctness of the computation.

To complete the proof, the prover runs the FRI protocol to show that this polynomial is low degree.

Finally, the prover outputs a STARK proof that contains all the Merkle roots, challenge values, and folded evaluations. This proof can be verified directly or used inside another circuit for recursive verification, which is how Eigen’s zkVM proves large computations efficiently.

The Vulnerability

In the FRI protocol, the verifier samples random indices during each folding round using a Fiat–Shamir transformation over the Merkle root. However, the current implementation fails to ensure that the sampled indices are collision-free across rounds. The implementation does not prevent collisions after index reduction across folding rounds (i.e., indices that map to the same coset in later rounds).

This introduces a vulnerability. Because index selection is solely derived from the merkle root, a malicious prover can sample evaluations in the codewords to change the merkle root and cause index collisions. Thus, the underlying polynomial can be changed to have a lower degree than it actually does.

Specifically, this line in Eigen’s code:

let mut ys = transcript.get_permutations(self.n_queries, self.steps[0].nBits)?;Here, the sampled indices are derived from the Merkle root of a codeword of length where each evaluation corresponds to a leaf in the Merkle tree. Since the Fiat–Shamir seed (and therefore the indices) depends only on the Merkle root, a malicious prover can repeatedly alter the leaf values until the resulting Merkle root produces a set of indices that cause a collision.

If collisions cause the verifier to repeatedly check the same reduced-domain locations, large portions of the domain may remain unchecked. This allows the prover to craft a proof for a different polynomial that still appears valid but has a much lower degree. As shown in our PoC, we construct a different polynomial of much lower degree:

// PoCif si == 0 { let mut new_pol = vec![F::ZERO; 1000]; for i in 1..1000 { new_pol[i] = pol[i]; } new_pol[0] = F::from_vec(vec![FGL::from(fiat),FGL::from(fiat), FGL::from(fiat)]); let mut roots = standard_fft.roots[11].clone(); roots.truncate(1000); let mut new_poly = lagrange_coeffs(&roots, &new_pol); new_poly.resize(pol.len(), F::ZERO); pol2_e = standard_fft.fft(&new_poly);}In the broader context, this means an attacker could construct a proof that passes verification even though it represents an incorrect computation. Thus, we can prove wrong outputs for any given input. On a blockchain, such an exploit could potentially enable invalid state transitions such as double-spends, forged executions, or arbitrary state updates.

In the intended protocol, sampled indices must be unique to guarantee that each part of the codeword is independently checked.

The Fixes

The goal we want is to ensure the verifier’s spot-checks remain independent by preventing two sampled indexes from colliding at any round. At the same time, we want to do this while preserving Fiat–Shamir determinism for both the prover and verifier.

The Anatomy of a STARK blog has a relatively simple patch. Instead of sampling all indices in one batch and risking collisions, the FRI implementation in the article samples indices iteratively, checking for collisions as it goes. We can see from the code here.

def sample_index( byte_array, size ): acc = 0 for b in byte_array: acc = (acc << 8) ^ int(b) return acc % size

def sample_indices( self, seed, size, reduced_size, number ): assert(number <= 2*reduced_size), "not enough entropy in indices wrt last codeword" assert(number <= reduced_size), f"cannot sample more indices than available in last codeword; requested: {number}, available: {reduced_size}"

indices = [] reduced_indices = [] counter = 0 while len(indices) < number: index = Fri.sample_index(blake2b(seed + bytes(counter)).digest(), size) reduced_index = index % reduced_size counter += 1 if reduced_index not in reduced_indices: indices += [index] reduced_indices += [reduced_index]

return indicesThe seed (from Fiat–Shamir) is concatenated with the counter and hashed using BLAKE2b to generate fresh index bytes. After generating each index, the algorithm checks whether its reduced version (the index modulo the size of the reduced domain) has already been used. If it hasn’t been used, it’s accepted. If it has, the counter increments again and a new hash is generated until a unique one is found.

Since the Fiat–Shamir seed is identical for both prover and verifier, the increment rehashing process will produce the same set of unique indices on both sides. Any skipped or regenerated indices occur deterministically, so the prover and verifier remain synchronized. This guarantees consistency while ensuring that all sampled indices remain independent.

In the case for Eigen, we suggest adding this loop into the index generation code in both prove and verify. This patches the vulnerability.

Conclusion

FRI’s soundness relies on the independence of sampled indices. Once collisions are allowed, the degree bound argument collapses, and false proofs become possible. By neglecting to enforce collision-free index selection, Eigen’s zkVM prover allows attackers to construct proofs for invalid computations while still passing verification.

Fortunately, the fix is straightforward. Iteratively sampling indices and filtering out collisions, as shown in the patch above. It ensures that each verifier spot-check is truly independent.

As zero-knowledge systems continue to evolve and integrate more into scalable blockchain infrastructure, implementation review remains essential. Even one missing check, like the index collision filter in FRI, allows for proof forgery. At Veria Labs, we believe this demonstrates the importance of continuous auditing and testing for all systems.